This Christmas, I volunteered on the Greek island of Lesvos to do what (little) I could to improve the situation of the thousands of middle eastern refugees making their way toward Europe and a (hopefully) better and safer life. From December 23-29, I explored, volunteered, donated, and learned a lot, ranging from the little (a few Arabic phrases, “selfie” is also how you say it in Arabic, bananas are definitely a favorite fruit among the refugees I met…) to the life-altering:

1) Refugees need help, but they are not helpless.

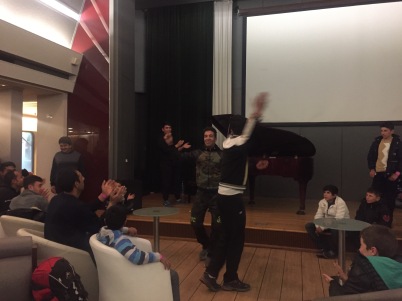

Let’s not sugarcoat things: getting in a questionably seaworthy and definitely overwhelmed rubber boat with (maybe, at most) a backpack of your belongings to cross a freezing and potentially dangerous stretch of the Aegean Sea is terrifying at best. If you factor in the trials, confusion, and price most had to endure before even boarding the boat, the feat becomes nothing less than Herculean. Understandably, many refugees arrive cold, wet, hungry, dehydrated, confused, scared, and quite simply and literally exhausted. It is true, they need help, just like any of us would after enduring the same thing. Most of the immigrants I met were happy to accept water, warm clothes and food, and a spot next to a campfire while they recovered. But after that, they could handle things pretty well on their own. Once they were warm, dry, and safe, they wanted to charge their phones to call their families, get registered so they could legally take taxis and stay in hotels, and then set about reintroducing even a semblance of normalcy into their lives. Many of the immigrants/refugees I met had at least a basic understanding of English, were very polite and cooperative, and had their own money to spend on whatever they needed or wanted. They gladly accepted what we could offer (I mean who wouldn’t after the hell they’ve been through?) but to me it was very clear that they are intelligent, flex ible, resourceful, brave, and very capable of handling themselves. Not only that, but they were happy. On the 16-hour ferry back to Athens from Lesvos, I found myself the only non-immigrant on the entire ferry (apparently most volunteers fly to and from the island?) Despite the exceedingly rude Greek ferry employees (looking at you, Hellenic Seaways), the refugees found a piano, a pianist, and had themselves a little party on the sea. As I watched them dance through my eyes that could barely stay open, I was amazed by their resilience and optimism.

ible, resourceful, brave, and very capable of handling themselves. Not only that, but they were happy. On the 16-hour ferry back to Athens from Lesvos, I found myself the only non-immigrant on the entire ferry (apparently most volunteers fly to and from the island?) Despite the exceedingly rude Greek ferry employees (looking at you, Hellenic Seaways), the refugees found a piano, a pianist, and had themselves a little party on the sea. As I watched them dance through my eyes that could barely stay open, I was amazed by their resilience and optimism.

If only these characteristics, along with luck and hard work of course, guaranteed them future success. It seemed to me the only thing rendering the immigrants and refugees helpless was the European Union’s and Greece’s paralyzingly frustrating laws regarding asylum and naturalization. More on that later.

2) Do not trust the media

The media (especially Western media) loves a sob story. They know anything that pulls at our heartstrings = profit, and they have no problem wringing every last cent out of our emotions. Luckily, the media’s tendency to exaggerate is the reason many volunteers (myself included) decided to go and do what we could to help. The obvious misfortune, of course, is that what we see on tv are the extremes: the drownings that happen during the crossing, or the successful fairy tales of those who have managed to settle in Germany or America or other idealized destinations.

For example, Day One in Lesvos, I arrived to Eftalou on the north coast red-eyed and disoriented after an overnight ferry from Athens. I was astonished to see Turkey right there, close enough to make out detail. The distance from the beach where I stood to the Turkish coast looked about the same distance from shore to shore of the lake I used to swim across as a kid. A kind British volunteer I met named Cookie informed me that the crossing from Turkey to that particular beach usually takes about an hour, if the sea is calm and the motor doesn’t stall. This information shocked me; the media (or maybe my own geographical ignorance when it comes to this part of the world) led me to believe the crossing would be a more lengthy sojourn. I pictured families starving, huddling, confined to this little boat all day and night and was surprised and relieved to know that on the north of the island, the crossing typically takes 1-4 hours.

Another common misconception is the state of the island due to its reception of so many refugees. I was told that September and October were much more chaotic and exhausting for everyone, as each day 50-100 boats arrived all over Lesvos. When I arrived, the state of things was very different; during my two days on the island’s northern coast, only 10ish boats arrived per day (probably due to the harsher winter conditions and the fact that the Turkish coast guard had become increasingly vigilant and cruel). I am certain the situation has been very difficult and disheartening, but during my short time on Lesvos, I was pleasantly surprised by how many volunteers there were, how streamlined the process had become, and how much help everyone was receiving. I expected to see people lying on the sides of roads to rest, or sleeping in whatever natural shelter they could find. This was not the case. At Skala Sikaminea, there were more volunteers than refugees and we spent more time cleaning and sorting clothes in preparation for their arrival than anything else. At Pikpa/Village of All Together, it was the same story. It warmed my heart to see that every refugee family there had its own sufficiently large outer-space looking tent, where they had a small kitchen, beds, and a welcoming community of both fellow immigrants and volunteers. I wondered why the media wouldn’t report that the situation was improving on the island.

3) Ethics and morals are very subjective and situational

The more I learned about the crossing experience, the volunteer politics on the island, the simultaneous strain and support the refugees imposed on Lesvos’ economy, and the treatment the immigrants received from both the Turkish, Greek, and other European authorities, the more warped my sense of right and wrong became.

First and foremost, I grew to loathe bureaucracy. Granted, I already hated it, due to my experiences dealing with Spanish embassies and US government and the normal, healthy amount of dread everyone feels when going to the social security office or the DMV in America, but on Lesvos it is incomparable. The love child of simple xenophobia and backwards ideas of self-preservation, the bureaucracy prohibiting humane conditions for newly arrived immigrants on Lesvos fucked everyone over. The rules are simple and stupid: before registering at internment camps like Moria (southeastern Lesvos), the immigrants and refugees cannot legally ride in taxis or pay for hotels. This is a problem because many refugees arrive on the north side of the island at Eftalou or Skala Sikamineas, and must register at Moria or Mytilene. It seems to me that the already strained Greek economy would benefit from a huge surge in demand for taxis and hotels, especially during the low season for tourism. I made friends with the man who owned the hotel I stayed in and he taught me a lot about the Greek perspective on the refugee crisis. His name is Vakis and he is a typical Greek businessman: tourism-minded, gregarious, and generous. When we discussed the situation, he told me he was happy to rent his rooms to volunteers, but had to request that they didn’t house any refugees. Even if the rooms were empty and the refugees could pay, he was not allowed to rent to them for fear of legal repercussions against his business. The government prohibited it. The government also prohibited a private volunteer from transporting refugees in their own car, without calling and registering the action with the police. The situation has improved somewhat, however. In September and October, refugees had to walk from the northern coast to Moria/Mytilene, which was an annoying drive and a brutal walk. Now, there are charter buses driven by very grumpy Greek drivers who come to Skala Sikamineas and Eftalou to transport the immigrants to “stage two” camps where they can receive clothes and other necessities before moving to the internment and registration camps to wait days or weeks to be registered. In my opinion, it would be better for everyone if the refugees who could afford it were allowed to stay in hotels while awaiting registration, buuuuuuuut what do I know?

While on the island, I also felt a strong sense of role reversal; the good guys had become the bad guys and vice versa. I had always thought, because the collective American conscience has dictated it, that smuggling anything, especially people, is an inherently bad thing. In the same stupidly naive way, I have been trained to see authority figures like the police and coast guard in a good way (ostensibly they exist the protect our safety). While on Lesvos, I realized the opposite. The Turkish smugglers who help the refugees cross, for example, are often vilified for charging 1000€ fare per person to be transported illegally to Greece. The more I thought about it, the less unreasonable this became. Considering that the supply for rubber boats is probably quite low, and every motor costs around 1000€, and the fact that their service is very illegal, it makes sense that they would charge more. I do believe it is quite cruel of them to overload the boats to such a dangerous degree, but when trans portation services are driven by profit, this is a universal norm. According to Vakis, there are many groups that like to exploit the refugees’ illegal status for a hearty profit. He told me about Albanian immigrants who have come to Greece only a generation or two ago who also capitalize on how much it sucks to be an illegal immigrant. According to him, they have made a business of using their own cars as illegal taxis for immigrants, and they charge exorbitant prices. For a legal taxi and a legal citizen or tourist, a taxi from Skala Sikamineas to Mytilene would cost about 80-90€. The Albanian Greek citizens charged around 200€ for the same ride to an illegal immigrant or refugee newly arrived on the island.

portation services are driven by profit, this is a universal norm. According to Vakis, there are many groups that like to exploit the refugees’ illegal status for a hearty profit. He told me about Albanian immigrants who have come to Greece only a generation or two ago who also capitalize on how much it sucks to be an illegal immigrant. According to him, they have made a business of using their own cars as illegal taxis for immigrants, and they charge exorbitant prices. For a legal taxi and a legal citizen or tourist, a taxi from Skala Sikamineas to Mytilene would cost about 80-90€. The Albanian Greek citizens charged around 200€ for the same ride to an illegal immigrant or refugee newly arrived on the island.

The authorities, who are supposed to be “the good guys” also left me quite disillusioned. I never saw it myself, but heard stories from other volunteers of the Turkish coast guard circling refugee boats during the cross and threatening to open fire on them. The Greek authorities too have been known to be quite unhelpful, to the point where it had become a common practice for the refugees to use knives to pop a rubber boat the second it arrived on Greek land so that no one could force them back into the boat and back to Turkey.

And the cycle of misplaced responsibility and intolerance just escalates as you climb the political ladder:

- Turkey received $3 billion to stop sending refugees. Because receiving legal money to stop an illegal service makes total sense, right?

- http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21679333-refugees-misery-still-drives-them-leave-europe-has-deal-turkey-migrants-will-keep

- European powers even approved the use of military force against boats found in international waters. Because an effective way of ending such a state of emergency is to further abuse its victims. Good idea!!

- http://europe.newsweek.com/eu-approves-military-action-against-mediterranean-smuggler-boats-report-332954

- Hungary refuses refugees – is building a fence to keep them out and punishing illegal border crossing with up to a four year jail sentence. Solidarity, Hungary!

- http://europe.newsweek.com/europes-new-migration-frontline-opinion-divided-how-stop-crisis-332188

- The politics surrounding the definition of “refugee” is especially heartbreaking. The official definition seems to be quite inclusive but is actually vague enough to allow nations to create their own criteria: “…owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” …one would think this definition would cover anyone desperate enough to cross the Aegean in an overloaded rubber boat, but in practice it actually doesn’t. According to my observations in Lesvos, you are only guaranteed asylum if you have a Syrian passport (maybe Afghani) and are literally fearing for your life. For example: the old man I met with a broken hand and three sons who had to be reassured multiple times that no Islamic State member would kill him or recruit his sons is probably a shoo-in for asylum, but the status of the family who fled as a preventative measure might be a bit iffy.

- http://www.geneva-academy.ch/RULAC/international_refugee_law.php

- Complete lack of unity. Germany wants to accept hella refugees (Holocaust guilt?) but Hungary is one collective asshole. Europe needs solidarity. Accepting immigrants is a team sport; if one or a few countries take on all the burden it will certainly upset the balance that the European Union strives to create.

- http://europe.newsweek.com/europes-mixed-reaction-migrant-crisis-331853

Another source of mental contention for me was the self-righteous bitterness felt between NGOs, upstart volunteer programs, and freelance volunteers alike. There was definitely an us-versus-them mentality that was both understandable and unsettling. The primary complaint of the established NGOs seems to be that there are too many freelance solo volunteers and upstart volunteer organizations that swoop in without fully understanding the process and as a result give refugees incorrect or outdated information while simultaneously stepping on the toes of the larger NGOs and island inhabitants. But the opposing perspective is equally compelling, arguing that the NGOs are too picky about which help they choose to receive and can be too unwieldy and inflexible to do any real good due to their large sizes and bureaucratic structures. One volunteer friend I made specifically called out UNHCR’s charitable contributions as being “complete shit,” claiming they show up on the beaches at inconsistent times so they can give refugees blankets that boast UNHCR in huge letters. In her opinion, it was more of a publicity power play than actual altruism. Personally, I can sympathize, given my initial frustration when searching for a program with which to volunteer my time. UNHCR and several other NGOs I researched required a minimum time commitment (usually a month), and extensive background checks and training. Given my time constraints and aforementioned rancor for bureaucracy, my mental monologue was something like, “this is bullshit; there is no way I can’t be useful if I just show up.” So that’s what I did. And it worked very well. Taking cues from a few other volunteers I met, I described myself as a “short-term freelance volunteer,” which always received a few chuckles. I enjoyed the freedom to satiate my own curiosity by visiting several refugee-dense sites around the island and was never met with disdain. My favorite spot was at the Lighthouse beachfront camp at Skala Sikamineas, where one long-term volunteer actually thanked me with a hug when I mentioned that I wasn’t with an organization, but just showed up to do what I could. (Important to mention that I could not have done it without you. If you donated to my GoFundMe campaign, thank you for helping to make my mission a reality and I hope you find this post interesting and informative.)

Hi! I was wondering if I could use one of your photos on a website. I am leading a team of volunteers to Lesvos in August and I’m trying to set up a website now, but I haven’t been there and I need a cover photo. It would be so cool to use the picture of the deflated boats in Skala Sikamineas because that is where we will be serving!

Thanks for going and serving there, it’s such an important place to be right now and I can’t wait to go!

Thanks

LikeLike

yup I am sending you an email right now! (make sure it didn’t go to the spam folder) =]

LikeLike

Thank you so much! You rock!

LikeLike